Term used to refer to the artistic productions of people who suffer from chronic major psychoses, such as schizophrenia or manic depression. These untrained artists inexplicably begin to be creative, sometimes la te in life, producing bodies of work with acknowledged aesthetic value. Psychotic artists are often noted for their unceasing creativity and single-mindedness during the execution of their works; it seems that in some cases a psychotic artist sees the works of art as the main justification for his or her existence. Psychotic art is usually produced in mental hospitals. The institution may be supportive and encouraging to the artist and conserve the works, but sometimes works have been overlooked or even destroyed, as in the case of the stone sculptures of Adam ‘The Highlander’ Christie (1869–1950), which were broken to make a car park at Sunnyside Royal Hospital in Montrose, Scotland. The type of mental illness suffered may influence the imagery characteristic of a particular psychotic artist. It has been noted that children with autism often depict extraordinarily realistic details, such as always showing knee-caps in portraits or a myriad of abstruse architectural details.

te in life, producing bodies of work with acknowledged aesthetic value. Psychotic artists are often noted for their unceasing creativity and single-mindedness during the execution of their works; it seems that in some cases a psychotic artist sees the works of art as the main justification for his or her existence. Psychotic art is usually produced in mental hospitals. The institution may be supportive and encouraging to the artist and conserve the works, but sometimes works have been overlooked or even destroyed, as in the case of the stone sculptures of Adam ‘The Highlander’ Christie (1869–1950), which were broken to make a car park at Sunnyside Royal Hospital in Montrose, Scotland. The type of mental illness suffered may influence the imagery characteristic of a particular psychotic artist. It has been noted that children with autism often depict extraordinarily realistic details, such as always showing knee-caps in portraits or a myriad of abstruse architectural details.

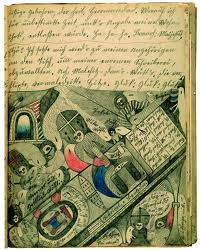

The work of each artist is entirely individual, with an instantly recognizable subject-matter or style. Aloıse Corbaz (1886–1964), who has now been recognized as a significant artist, began drawing at the age of 55. She depicted romantic rites such as Love Scenes with Sphinx-Mary Stuart (Lausanne, Pa l. Rumine), Ophelia as a Mermaid and Cleopatra as a Snake Queen. Heinrich Anton Müller (1865–1930) drew lifelike but distorted sinuous people and beasts, such as his Figure with Goat and Frog, which have astonishing qualities of singularity and strangeness. He also created three-dimensional machines purported to ‘produce energy’. Psychotic artists tend to utilize only basic tools and media, though sometimes not simply on account of availability. Adam Christie was offered hammer and chisels by the sculptor William Lamb (1893–1951) but kept using a nail and broken glass. Aloıse Corbaz wrote in 1919: ‘I collect paper from the rubbish bins, and scribble in the lavatory’. She used coloured pencils if available or otherwise geranium petals and leaves, or toothpaste. Angus McPhee, forty years in a psychiatric hospital, devoted every moment of his free time to making garments from sheep’s wool and grass he had spun. Heinrich Anton Müller drew with a thick, blue or black carpenter’s pencil on sheets of wrapping paper, sometimes sewn together. adolf Wölfli, whose work is lavishly conserved in a permanent repository at the Kunstmuseum in Berne, mostly used pencils to depict narratives and also made collages from magazine illustrations, thus incorporating references to the cultural life outside the asylum that was inaccessible to him.

l. Rumine), Ophelia as a Mermaid and Cleopatra as a Snake Queen. Heinrich Anton Müller (1865–1930) drew lifelike but distorted sinuous people and beasts, such as his Figure with Goat and Frog, which have astonishing qualities of singularity and strangeness. He also created three-dimensional machines purported to ‘produce energy’. Psychotic artists tend to utilize only basic tools and media, though sometimes not simply on account of availability. Adam Christie was offered hammer and chisels by the sculptor William Lamb (1893–1951) but kept using a nail and broken glass. Aloıse Corbaz wrote in 1919: ‘I collect paper from the rubbish bins, and scribble in the lavatory’. She used coloured pencils if available or otherwise geranium petals and leaves, or toothpaste. Angus McPhee, forty years in a psychiatric hospital, devoted every moment of his free time to making garments from sheep’s wool and grass he had spun. Heinrich Anton Müller drew with a thick, blue or black carpenter’s pencil on sheets of wrapping paper, sometimes sewn together. adolf Wölfli, whose work is lavishly conserved in a permanent repository at the Kunstmuseum in Berne, mostly used pencils to depict narratives and also made collages from magazine illustrations, thus incorporating references to the cultural life outside the asylum that was inaccessible to him.

The term ‘psychotic art’ does not include the work of those who have already worked as artists before becoming mentally ill, for example John Martin, Richard Dadd (for illustration see Dadd, richard), and Louis Wain (1860–1939). Their works produced while mentally ill, however, sometimes show the characteristics of psychotic art (Wain’s popular cats progressively and dramatically disintegrated during his schizophrenic illness), and some authorities do seek to designate these works as psychotic art, sometimes confusingly assembling both in the same collection. However, a distinction is possible between the two, in that professional artists who become mentally ill have a body of work created during normality, whereas the psychotic artists arrive at creativity out of utmost adversity, from which they often never recover. Aloıse Corbaz wrote: ‘I lament my waif-like state in the conflagration of this world. It is impossible to describe my moral and material misery.’ The Surrealists also compared their art to the work of psychotic artists, with whom they sometimes exhibited. The two are easily differentiated, however, by contrasting the striking innocence inherent in psychotic art with the provocative intention in Surrealism, where the practitioners occasionally sought abnormal states by drugs, starvation (e.g. Miró) or ‘auto-hypnosis’ (e.g. Dalí) to achieve their sophisticated effects. Doctors and professional artists together have won recognition for psychotic art, now esteemed when previously it was totally overlooked.

The term ‘psychotic art’ does not include the work of those who have already worked as artists before becoming mentally ill, for example John Martin, Richard Dadd (for illustration see Dadd, richard), and Louis Wain (1860–1939). Their works produced while mentally ill, however, sometimes show the characteristics of psychotic art (Wain’s popular cats progressively and dramatically disintegrated during his schizophrenic illness), and some authorities do seek to designate these works as psychotic art, sometimes confusingly assembling both in the same collection. However, a distinction is possible between the two, in that professional artists who become mentally ill have a body of work created during normality, whereas the psychotic artists arrive at creativity out of utmost adversity, from which they often never recover. Aloıse Corbaz wrote: ‘I lament my waif-like state in the conflagration of this world. It is impossible to describe my moral and material misery.’ The Surrealists also compared their art to the work of psychotic artists, with whom they sometimes exhibited. The two are easily differentiated, however, by contrasting the striking innocence inherent in psychotic art with the provocative intention in Surrealism, where the practitioners occasionally sought abnormal states by drugs, starvation (e.g. Miró) or ‘auto-hypnosis’ (e.g. Dalí) to achieve their sophisticated effects. Doctors and professional artists together have won recognition for psychotic art, now esteemed when previously it was totally overlooked.

André Breton referred to ‘the blind and intolerant prejudice under which works of art produced in asylums have suffered for so long’.  The French psychiatrist Lombroso collected the art of psychiatric patients to further his interest in what he described as ‘genius induced by mental illness’. Hans Prinzhorn, a German art historian and psychiatrist, insisted in 1922 that psychotic art deserved serious attention, concluding that mental illness can sometimes release creativity, and he collected over five thousand works by inmates of asylums in Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Austria and Italy, which are now at the psychiatric clinic at the University of Heidelberg. Dubuffet found a clear example in the art of psychiatric patients for his theories about Art brut and collected many pieces (now Lausanne, Col. A. Brut). He claimed that the works, while often rudimentary, ‘are charged, perhaps more strongly than the works of celebrated artists, with everything that could be asked of a work of art: burning mental tension, uncurbed invention, an ecstasy of intoxication, and complete liberty’.

The French psychiatrist Lombroso collected the art of psychiatric patients to further his interest in what he described as ‘genius induced by mental illness’. Hans Prinzhorn, a German art historian and psychiatrist, insisted in 1922 that psychotic art deserved serious attention, concluding that mental illness can sometimes release creativity, and he collected over five thousand works by inmates of asylums in Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Austria and Italy, which are now at the psychiatric clinic at the University of Heidelberg. Dubuffet found a clear example in the art of psychiatric patients for his theories about Art brut and collected many pieces (now Lausanne, Col. A. Brut). He claimed that the works, while often rudimentary, ‘are charged, perhaps more strongly than the works of celebrated artists, with everything that could be asked of a work of art: burning mental tension, uncurbed invention, an ecstasy of intoxication, and complete liberty’.

Text from Grove Art Online.

Recent Comments

pete says,

thank you very much this was very helpfulH M Yamada says,

There is something dire, dangerous and mysteriously compelling about these ...

Robert Horvitz says,

Belated thanks for citing my work! I have a newer ...

article/about says,

Berber as well as Arab nomads took their caravans of ...

Betty Wood says,

Sometimes when I create something beautiful I feel like someone ...